In our ninth grade world cultures class, we studied a different region of the globe each quarter. I remember the textbooks. Slim volumes of different colors, a country’s name printed in white text against the backdrop. A stock image photo of the Kremlin, the Great Wall. Russia, China. The first quarter we studied India. The next it was Africa. I didn’t necessarily recognize at the time that while most of the books covered a single country in and of itself, the African one was devoted to the full continent, all fifty-four countries. For one of our first exams on Africa, we had to label each of these countries with the correct name and spelling. To study, I color-coded the map and memorized each nation. I did well on the test, though like most of my precollegiate examinations, what I learned for the test, I didn’t retain, and I often have to look up the locations of smaller countries still when they’re referred to in a news story. Most of our elementary and secondary education system, at least at the time in which I engaged it, relies on rote memorization, and this I did recognize, even back then. Critical thought wasn’t encouraged, or at least, it wasn’t encouraged in any kind of widespread fashion. But some of the teachers asked it of us. And one of these teachers was Mrs. Holland.

Mrs. Holland already made an appearance in these pages. In case you’ve forgotten, she was the one who defended Delia Birch when the kids accosted her with whispers of “espionage” from the back of the classroom. She was the one who talked to us in the aftermath. It was part chastisement, but it was also encouragement. Encouragement to think critically. I’m not sure I recognized it at the time—there are so many things I can say this of, things I didn’t recognize, but that registered; seeds that were planted and germinated; things that led me in the right direction even if I didn’t know it—but she was telling us not to follow blindly. To resist doing as you see others doing simply because it’s convenient, expedient. This is difficult as a teenager. I’m not sure it’s any less difficult as a younger child and it’s maybe only a smidge less difficult as an adult. The power of the group is persuasive. The lock step and rhythm that popular thought encourages one to fall into, especially when being assailed by choices on all sides, choices we maybe haven’t had sufficient time to ponder and weight the pros and cons of, let alone research and form informed opinions about. It’s been my experience that people don’t like to be caught uncertain or be seen as lacking in knowledge. It makes us feel ignorant to say, “I don’t have the answer,” so we pretend to know things we don’t. We might allow those who argue more persuasively to form opinions for us. Simply so that we have one. So that we feel a part of something. It seems a human attribute that we’d rather be resolute in our ignorance that abstain for lack of knowledge. And make no mistake, I say “we” because I can be just as guilty of this.

This is, of course, abstraction. But in memory, this abstraction finds its first concrete example in the mock-OAU meeting we held in Mrs. Holland’s class. For the week, we arranged the desks in a circle and stared out on an orator in the center. OAU was short for the Organisation of African Unity, and our assignment was to write a resolution and present it to the committee for a vote. Despite having studied Africa all quarter, I still didn’t feel that I knew about it well enough to draft a resolution, and this terrified. And just as I had with Miss Vart’s social studies assignment back in eighth grade, I concocted something with enough muster to pass but ultimately forgettable. I can’t even recall which country I was supposed to represent. It might have been Somalia. I might have even picked Somalia, since I’d seen it on the news, and I might have presented a “feed the nation” package, since that’s what everyone knew and my resolution would get approved. Minimal work; passing grade. But I might be making this up.

What I do remember is Dan Abrams standing before the class, making an impassioned plea for a unified language. “The problems of Africa,” he argued, “stem from misunderstandings in communication. There are between 1,500 and 2,000 languages spoken on our continent. What I’m proposing is the creation of a unified continental language for all Africans. A language that resolves these miscommunications and allows us to come to the table as equals.”

What he presented, of course, was the dream of Babylon. An immediate understanding of tongues. From a logical perspective, his proposal made sense. Why not create a universal language that all people could speak? A language that would allow communication across borders, across nationalist barriers? The result was so obvious, why was it a classroom full of thirteen and fourteen year olds could reach it while adults hadn’t been able? I didn’t know anything about it. I’d never spoken to anyone who didn’t speak English. I’d always been understood. But it sounded good to me. I made a quick decision to vote yes for his resolution, as I’m sure others did. It seemed a no-brainer. America had an official language. Sure, there were people who spoke Spanish at school. Some of the kids spoke Korean. A few of the kids even spoke Chinese. But classes were taught in English, right? This was a great idea. When the vote was taken, however, and the resolution passed unanimously, Mrs. Holland sat in one of the student desks and looked crestfallen. We’d seen that look before. It was the same look we’d received when none of us had stood up for Delia Birch. She closed her eyes and shook her head and paused a moment before she spoke.

“Class,” she said. “I’m appalled. I am simply shocked and appalled by your vote.” She stood up. “Do you understand what language means? Do you understand how important it is? It’s a source of identity. It roots people in their culture. To simply strip them of that and replace it with a universal language is irresponsible at best. How would you feel if someone came into this class and told you that you couldn’t speak English anymore? How would you feel if the tool you used to communicate with your family and friends your whole life was taken away from you? This is what you’ve elected to do. To diminish the beauty we find in difference, the richness. You’ve voted for a more cohesive world, but a less beautiful one.”

We sat in stunned silence. Somehow Mrs. Holland knew how to strike at our hearts, our emotions. She wasn’t treating us as children. At least, I didn’t feel that way. She was talking to us like adults who’d made a bad decision. She was hoping to sway us, to change our minds. She was offering an appeal to our better natures and senses, just as she had with Delia Birch. Of course, the responsibility we were being imbued with, even if imaginary, was somewhat ridiculous. A class of predominantly white American teens diagnosing and discussing the ills of Africa. But to linger on this misses the point of the assignment, which was to learn about the countries there, to identify their hardships, their difficulties, and empathize. By doing so, I believe Mrs. Holland hoped we’d gain some understanding or insight into the lives of others, how the problems of a nation couldn’t be solve in one broad stroke. But if our vote was any indication, we’d failed. One of the problems, naturally, was that in preparation we’d read only a textbook, Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, and Alan Patton’s Cry, the Beloved Country. This taught us factual information, colonialism and apartheid, all of which had far-reaching impact on contemporary Africa, but none of which detailed the problems as they existed in a temporary setting: government corruption, civil war, the West stripping these countries of their natural resources. Of modern Africa, we knew only the sickly children with flies on their eyes we saw in infomercials. And so to make a mock OAU of us made a mockery of the OAU. But I don’t blame her.

Maybe she would have taught us more if she could have. But government corruption and American exploitation weren’t approved themes in our ninth grade class. Nevertheless, she pointed us in the right direction. While Miss Vart had gone apoplectic at Jason Kim’s pretzel presentation, which to me meant she’d eschewed mention of racial or cultural differences, preferring to pretend they didn’t exist and we were all on big hands across America family, Mrs. Holland had deemed that our differences didn’t separate us, but enriched our lives. That having various languages was a beautiful thing. And we’d opted instead for homogenization. The word fascism hadn’t been uttered, but what we’d voted for might have only fallen one step short of it, the hive mind. And we’d voted this way because we’d only seen the benefits of a common language. Not one of us had stepped back to contemplate what the differences might have been. Who would have controlled the universal language, the way that might work to reinforce preexisting power structures and continue to disenfranchise people. How might the language form. Would the dominant tongue use this measure to erase marginalized people. It was easier too when one looked around and saw the rest of the class voting yes to simply raise my hand. We, as ninth graders, didn’t have enough knowledge of history to understand how stripping people of their language had worked in the past. How it had been used to divide slaves and make it more difficult to rebel when they were brought to the US. And I hadn’t read enough literature yet to know how language could be used to resist submission, to fight back. And though I couldn’t foresee how Mrs. Holland’s retort that day would affect me later, I became more curious about the world. I read as far and wide as I could, literature from all cultures all over the globe, anything I could get my hands on. I explored film beyond mainstream Hollywood or independent American cinema. I started to see music a different way. I noticed that even the language of hip hop was being used to resist the dominant discourse. It didn’t happen at once. It happened slowly. It was an evolution rather than revolution. But I believe the seed was sown that day. And this is what the best of teachers provide. Not merely knowledge, but the means to evolve.

Which doesn’t mean I learned not to follow blindly right then and never did it again. The struggle is constant. It is, of course, why the arts are so important. They teach us to think, question, show us a window into other lives. It remind us that we alone aren’t the world, that it’s much larger than we see day-to-day, that it’s larger than any one of us can hold.

*

As I’ve been writing this, I find myself disappearing into the past. I might have alluded to this already. But once I finished junior high I had to take a break, set some distance, remove myself from my youth. Part of this is that I have responsibilities toward my wife and my children. My wife has pointed out the disappearance. “You’re in the room with us,” she says. “But I can see you’re somewhere else.” At times, it makes me happy, stepping back, thinking of Lex and Elisa. Our music. Learning to create with a friend. Learning to live life. At others, I feel vulnerable. I don’t wish I’d made different decisions necessarily, but I miss him sometimes. If you’re reading these words, you may wonder why. Jim Lyons, for example, was the better friend to me, if your measure of a friend is someone who’s there for you when you’re suffering, when you need them. Someone who stops by to check on you and cares about your well-being. And yes, this is one type of friendship, a type I value deeply. It’s the reason we’re still friends. I credit the day with him at the bookstore with saving me from my anxiety and depression. True, I fought it to spite Lex, but if he’d never shown up, I never would have had that motivation. But this, in itself, pinpoints what I miss about Lex when I think about him. No one has ever challenged me the way he did. I’ve made friends with writers over the years whose work I respect, writers with whom I have report and exchange work. But they’re not trying to do the same thing as me. We’re not in direct competition. Lex and I, when we formed our band, had the same goal in mind. We wanted to create great music, and to this end, we both wanted to be a better songwriter than the other. I believe this made me push myself. And I’ve never had this relationship with anyone else. Maybe you only get it once in your life if you’re lucky. Maybe, in helping to give me drive, in helping to steer me in a certain direction, the brief time we shared was all I needed. It’s ingrained in me now, the type of work ethic we shared. But I miss trusting someone enough to let him to look at me after I’d showed him lyrics or played him a riff and say, “That’s terrible.” Sure, there are others that could do this. But there’s no one whose opinion I respect like I once respected his. And this esteem was mutual.

It’s possible the past is best left in the past. Yet, I’m compelled to keep coming back to it. As soon as I started this, I wasn’t able to stop. I tore through those first few chapters, composing what amounts to about half a novel in a little over a month. To some writers, this is nothing, but to me, it’s a breakneck pace. I can’t keep it up without exhausting myself. I’m far more emotionally drained in accessing these memories than I’d expected to be. Then, too, drafting this live (and please, make no mistake, this is a draft; if you see awkward sentence constructions or typos, this is the reason; I do a quick proofread before posting but it’s hardly a comprehensive edit) changes the way I write. There’s a reason they tell you to never show a work in progress to an audience: it makes the writing increasingly difficult. For all the positive comments and feedback, the compliments to my memory, people thanking me for sharing this story, one glib remark is all it takes for self-doubt to creep in, for me to get derailed (even if the person making that glib remark misunderstands what I’m trying to do here). This isn’t simply nostalgia or a celebration of any one moment or event in high school, but a chronicle of friendship. Sometimes I frame this as I experienced it then. At others, I frame it in retrospect, but in both cases, I hope to make such events part of a larger narrative. I’ve been writing and publishing for eight years. I’ve experienced my share of rejection, and I have the tools to muscle through self-doubt, to keep myself coming back, but that doesn’t make it easy. What am I doing this for? What does it mean? Why am I doing it? Do I have any talent at all? Should anyone even pay attention? All these things run through my head as I progress. And of course, all the while, I’m dealing with everyday life: taking my kids to daycare, working my office job, trying to be an attentive husband to my wife. And all the while, I’m compelled to return to this. By revealing myself and writing this story, I understand that I open myself to accusations of narcissism (there are elements of this in every memoir written). Yet, I’d counter by arguing that the revelation of self, our most tender parts, our weaknesses, can help others feel secure in opening up as well. That the mere act of writing, even a story as simple and uncomplicated as that of a friendship, makes people feel less alone.

I had a difficult time those first two years of high school. More difficult than some, not as difficult as others. While writing this, I learned that Delia Birch was autistic. This is one of those spaces I disappear into, something I’ve been contemplating. Another failure. And by failure I mean a failure for all of us. I see this now through adult eyes as a father. Her parents wanting the best for their child. She was different. Not pretentious different. Not feigning difference but really the same. She carried an affliction most of us can’t imagine. And because she had this affliction but still showed signs of being able to handle the school workload, still showed signs of functioning, her parents faced a choice: send her to a school for people with her affliction or trust in the goodness of other children and send her to a public school and hope the kids there treated her with kindness and understanding. More likely than not, this decision was difficult for them to make. But in the end, they decided to test the waters, to see how their daughter would fair and she did well. As I said, Mrs. Holland’s world cultures class was honors level, advanced placement. Delia Birch’s parents had placed their faith in their daughter. But they’d also placed it in us, in our better selves, our better natures, and we let them down. Part of this was ignorance. What did we know of autism back then beyond Rain Man? We weren’t told she was autistic. As I mentioned, I didn’t learn this until three weeks ago. We just thought she was weird. But her parents wanted their daughter treated like everyone else, and they gambled and they lost. And she suffered, but I only noticed her suffering peripherally because I couldn’t see beyond my own.

I’d entered the school year optimistically. Over the summer, I’d paged through the yearbook and read the signatures and looked at friend’s photos. I also picked out my clothes for the first day of school. Or, in my head, I knew what I wanted to wear. To pick them out and say, lay them on my bed, would have implied I cared and I didn’t want to seem that way to my parents or Lex or anyone. I wore my favorite shirt. A green polo shirt with vertical black stripes, black shorts. I was still wearing Airwalks even though I’d quit skating. And I had a Seattle Mariners baseball hat I adored. I was a Phillies fan through and through. But I liked the Mariners’ hat better, and since they were in the American League and the Phillies in the National—interleague play was still a decade or so off—I didn’t feel I was betraying my hometown squad. I had walked to the bus stop, the first on its route, and taken the big yellow school bus and met Kurt Grunwald and Mark Deeire who boarded at the next stop. Neither would play much role in my life, though I’d be on an intramural bowling team with Mark for a while in eleventh and twelfth grade. He drove our team to the alley, he was a nice guy, but I never got to know him well. We talked during the bus ride. Stupid nervous chatter, and once we arrived we split up. Lex wasn’t on my bus anymore, and Reed was gone. I went to homeroom and did the roll call. That first day the Freshman arrived early and had a half-day to acclimate themselves without the upperclassmen present. This made the day bearable since I got to see the friends whose signatures and pictures I’d gazed at in the yearbook. But I expected warmer receptions. I’d stop in the hall and nod and say, “How was your summer?” and they’d say, “All right” and maybe elaborate a bit. But I could tell right away there’d been a drift in our camaraderie. Part of this was that most of the friends I’d made the previous year weren’t in my classes. Lex was in none of them. He’d dropped French. We were in different levels of math. I had the one honors class, world cultures, and he didn’t have any. But even the standard level classes we should have shared, we didn’t. Most of the people I liked most were either in all three honors classes (world cultures, English, and science) or were stuck in remedial. The regular classes stuck me with people I didn’t know too well, and rather than try to get to know them, I rued the day I decided to pass up taking the exams to get into the two other honors classes.

Why hadn’t I taken the text, at least for English? I loved to read. I read voraciously and understood what I read. I did well on the reading comprehension portions of standardized testing. With science, I understood why I’d dodged the honors test. I’d never had much affinity for science. But why hadn’t I taken the English test? Maybe I did and didn’t pass. That’s a possibility. My grades in Mr. Blyweiss’s eighth grade Language Arts class were three Bs and an A over the four quarters. Maybe that wasn’t enough to gain access to the honors class. Had there even been a test? Or had they simply selected the students with the best grades, with all As. It’s possible they announced the test, and as usual, I wasn’t paying attention and didn’t find out until afterward. A number of things I missed owing to a propensity to daydream, to self-involvement, to living in my own little world. This, of course, had manifested in writing the occasional story. Beyond my fifth-grade genre exercise, “Slime in the Telephone Lines,” I’d joined a writing group at school in seventh grade, headed by the Reading Study Skills instructor Mr. Carroll. The first story I’d submitted was called “Antarctica.” It detailed a group of vampires living in caves in the Antarctic, hunting during the seasons of where dark overtook the land for days, months. It was essentially 30 Days of Night before 30 Days of Night without my bothering to conduct any research on the continent and whether the “days of night” happened there or elsewhere. Had I been a bit more savvy I would have set it in Alaska, Norway, Sweden. Somewhere far north. Somewhere with a population my vampires could stalk. Instead, they were in the middle of nowhere, where no one lived. They had no one to stalk, so I had to invent a population. I had intended the story to be dark, menacing, scary. I’d read Salem’s Lot by Stephen King in the sixth grade, and it was my favorite book at the time. I wanted to test that terror, to see if I could recreate it. And so I wrote and submitted it. And as often happened back then, I forgot I’d submitted or when the group was meeting or even that it existed until one of the student members approached me in the hall.

“Did you write that story about vampires in Antarctica?” she asked.

I had to search my mind a moment. “Yeah, that was mine.”

She congratulated me.

“It was so funny. We all laughed so much. It was supposed to be funny, right?”

She stood a moment, waiting for confirmation.

“Yeah,” I caught on. “Yeah, totally.”

This was the first time I’d been rejected for something I wrote. Or no, that’s not exactly right. I wasn’t rejected. I was accepted for the wrong reasons, which felt like rejection anyway. And it wasn’t the last time that would happen either. Still, I walked around the rest of that day feeling hollowed out. My story was stupid. I was stupid. And this was the way I’d walked the halls during most of my freshman year. My only refuge was playing guitar. My only sanctum, Lex’s room. He hadn’t yet moved downstairs to Ava’s spot. We were still upstairs in the back bedroom where we played. He’d done it up, too. Glow in the dark stars on his ceiling. A lava lamp. Some nights all of us would just lie around in the dark looking up at his ceiling, laying on his bed, me and Drew Schiff and Rick and Sonny Ford and Lex. Listening to music. We took turns choosing the music. Drew Schiff had taken to the first Counting Crows record, August and Everything After, and he played it a lot. I’d lie there and listen to “Perfect Blue Buildings” and think of how sad it was. How we were all striving to be something we’re not, perfect in the eyes of another. I wanted to be in love but wasn’t. I wanted to find someone to spend my time with, so I wasn’t lying in a bed with five dudes listening to Counting Crows on Friday night. I wanted to be perfect in some girl’s eyes, loved in return. But I didn’t love anyone. I didn’t even know who to set my sights on. And this left me adrift.

Drew’s cousin Tony P. was older than us. He got his license that summer, the one between eight and ninth for Lex and me, and when we weren’t sitting in Lex’s room on Friday nights, we were driving around, first in Tony P.’s dad’s Mercury Cougar, which we pushed to ninety one night on a stretch of Waverly Road and then when he could afford his own car, Tony P.’s Plymouth Horizon. The windows in the back were tinted and he got a new system put in, and we blasted Dr. Dre’s The Chronic (he only stopped pumping Chronic when Snoop put out Doggystyle; Drew would later get his license and his cassette tape of choice was Pearl Jam’s Vs., which seemed polar opposites). We thought we were bad-asses. We were testing limits, flirting with car wrecks, and some nights we might have had them if I hadn’t provided the voice of reason, “That doesn’t sound like a good idea.” Sonny Ford sat shotgun because of how big he was while Drew, Lex and I piled into the back seat and fought to not sit bitch, sandwiched between the other two. One night Sonny Ford brought a carton of eggs along and pegged people from the passenger seat. For a big guy, he was athletic. He had great aim. He nailed a guy with a leather jacket and we laughed and laughed at the angry look on his face, his receding form flailing about in the rear view mirror. But all that time, even when we laughed, even when our pulses raced with the speed we were doing, flying over the hills on Township Line Road late at night, I wished I was somewhere else, with someone else, though who I didn’t yet know.

It went beyond the yearning for a crush. It went beyond just liking a girl because she was pretty. I wanted these things, attraction, beauty. But it was more than that. I wanted intimacy. I wanted to be able to tell this girl things, whoever, she was. I wanted the same type of connection I had with Lex but with a girl. I wanted to have a love that would change my life, change me. In Mrs. Wolpert’s English class, I had read an abridged version of Great Expectations and was swept away with the romance of it. Pip’s yearning for Estella. The jilted Mrs. Haversham, so diminished and wounded by her rejection in love, that she charts her course as one of vengeance on men. Dickens had made love and yearning so dramatic. He’d made life seem so much more important in words than the one I was currently living. I wanted an Estella. Even if she wounded me. Even if I was rejected. I wanted to feel that deeply outside of a book, beyond words. And if I couldn’t have it there, then maybe I’d create it with my own words, but my medium was music, and I still wasn’t writing my own songs. Whenever I’d tried they came off as pale imitations of existing songs, better songs. Or they were overly complicated. Most of the songs I liked were about yearning and love. I tried to write about that, but the lyrics were hollow, cliche. I need to have someone to write about, someone to make it true.

That summer, the summer between eighth and ninth grade, Smashing Pumpkins had released Siamese Dream, and this record had hit me at the deepest levels. In the same way Achtung Baby had been the album we listened to all summer the summer before, Siamese Dream was the one I played over and over. Lex’s sister Ava had given him the Pumpkins first album Gish and he’d lent it to me, but outside of “Siva” and “Rhinoceros,” I wasn’t much interested. He claimed that the first record was better, but it was prelude. Dream was a masterpiece. It captured the wistful tone I felt over the summer and first year of high school, the yearning for connection, the dream of floating away. From the first single, the plexicolored video for Cherub Rock, I loved the sound. I put the record low on the CD player next to my bed when I went to sleep at night. I played it at a bit louder volume the next morning when I woke. I maxed it out midday. It had a strange quality of making me yearn for youth and innocence despite the fact I was young and innocent. Like I somehow had to recapture halcyon moments, and as the loneliness set in Freshman year, I felt it more keenly. Here was a record that spoke directly to me. I liked a lot of different music, eclectic music and I was letting new sounds in all the time, sometimes at Lex’s suggestion, sometimes at my parents or other friends. But if there were a music I wanted our music to sound like, this was it. I wanted to write songs that sounded like this, that moved like this, that moved me just like this. Still, I didn’t write any songs. I didn’t know how. Then one night, Lex and I started to try.

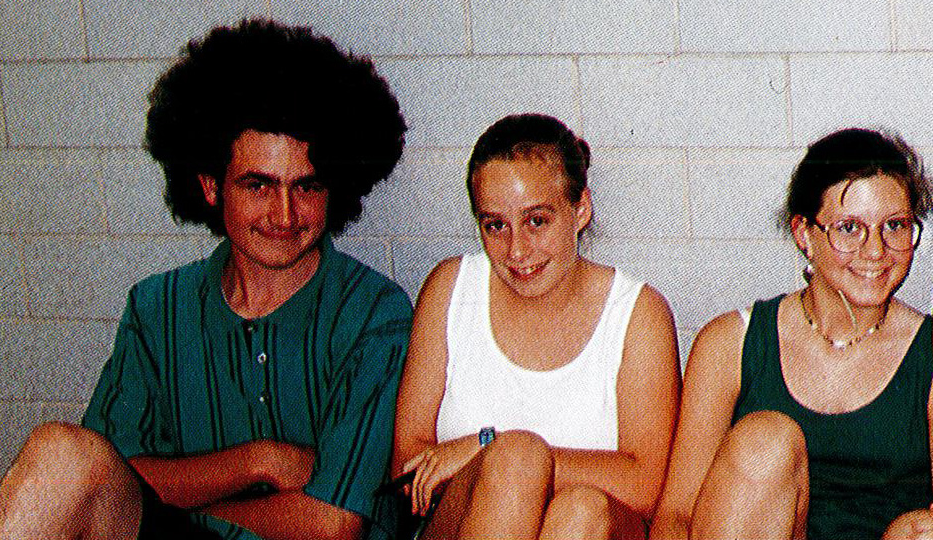

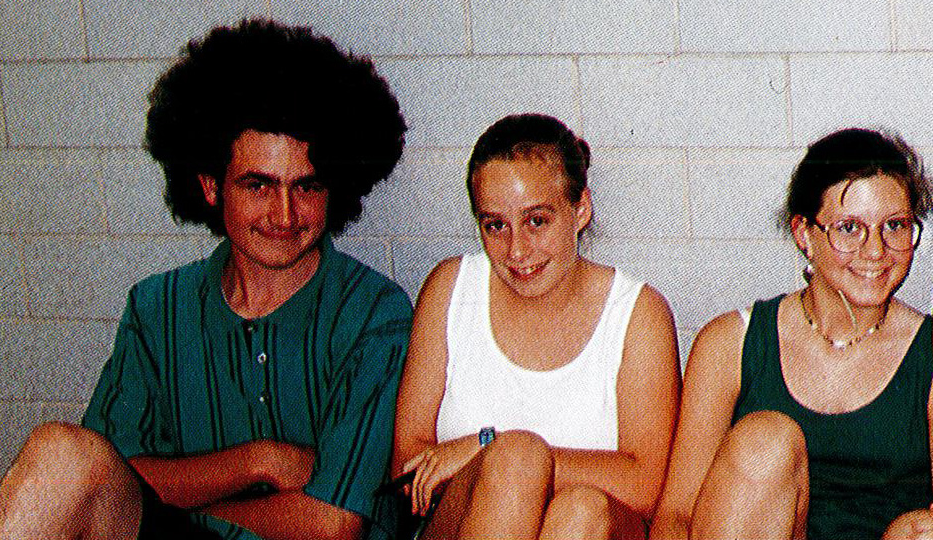

Some nights, our whole group sat in Lex’s room, but frequently it was the two of us. We tried inviting other musicians to play, but it rarely worked out. One night we’d invited Anne Schmolze, who I later became good friends with, to sit in with us. She had a nice voice and played guitar, but mostly she sat and listened to us, listened to me. I was probably trying to show off. I do this in front of people I want to like me. I had recently learned “Hey Joe” and I played it well and I liked to show people I played it well because playing “Hey Joe” required skill. So I ripped into it which likely didn’t make her feel at ease. This was one of my problems with making friends back then. I figured other people would like me because I was good at things so I tried to show off, when really it was much more likely they’d want to be my friend if I showed an interest in them. Most of the time when I did this, show an interest in someone else, it was really just someone I wanted to be acquainted with. As soon as I really liked someone, I talked too much, I showed off, preened. I still do it, too. Only now I know I’m doing it, and I tell myself, “Stop doing that,” and it’s like there are two versions of me: one that knows I should stop and tells myself to hold back and calm down and the other who can’t help himself. So even when we had a guest, someone new to play with, it didn’t last long and went back to being me and Lex quickly enough.

Lex took guitar lessons from a teacher named Rich at the Music Works. Rich was cool in a way Lex admired. He had a certain smile. He wore suits and shades. He carried his guitar like a session musician, though I couldn’t have cared less. For some reason I was resistant to the whole idea of lessons. I preferred, having taught myself, to continue doing just that. I figured it gave me a style all of my own. Of course, Rich taught him technical aspects I couldn’t figure out alone, but I picked up anything Rich taught him as soon as Lex showed it to me. My electric guitar, a black Ibanez, was a piece of shit by then. I hadn’t taken very good care of it, and the sound reflected this. So when Lex bought a Fender Telecaster with money he’d earned busing tables, I took over the imitation Gibson Es-335 his parents had bought him when he decided he wanted to play guitar. His parents were supportive of all his artists pursuits and helped him out when he decided music was his thing. They’d bought him the imitation Gibson and bankrolled the lessons. My dad had also been supportive and bought me an Ovation acoustic for my birthday, and whenever we weren’t playing loud, whenever night arrives and his parents urged us to quiet down, we put the electric guitars away and pulled out the acoustic. We played The Cure songs, “Killing an Arab” and “Boys Don’t Cry” and “Jumping Someone Else’s Train.” We played Nirvana. Lex had bought a drum machine and he’d programmed in the entire sequence of drums for “Come as You Are.” We played it in his living room when his parents weren’t home, swaying a bit to the side, like we were Nirvana, doing just as they did in the video. I had purchased a delay pedal, and we played Neil Young songs like “Down by the River” and “Cinnamon Girl” and I used it to create the same effects he did on his guitar solos. I played Hendrix, but Lex wasn’t up to it yet. He could follow the chord progression of “Hey Joe,” but that was all. When I tried “Little Wing,” I was on my own. Mostly, I was the one who sang. I wanted to be the singer but I didn’t know how to use my voice. At first I wanted to sound gruff like Kurt Cobain, then all whispery soft like Billy Corgan, and really my voice wanted to do neither.

One night, sitting in his room, talking, Lex broached the subject of writing our own material.

“We’re never going to get anywhere if we don’t write out own stuff,” he told me.

“Yeah, I mean, I’ve tried.”

But I hadn’t shown him anything. None of the songs I’d written were any good. And all were derivative. I’m not sure what I was expecting. That one day I’d wake up imbued with the magical gift of song craft.

“It’s like anything else,” he said. “We have to practice at it. You can’t expect to be good overnight.”

There went that idea…

“Have you tried writing anything?” I asked.

“No, but we should try now…”

“You mean, like right here, right now?” I said.

I started noodling the riff of that Jesus Jones song. Lex placed a hand over the fretboard to quiet me.

“Here’s what we’re gonna do,” he said. He pulled out his boombox. “I’m gonna hit record. We’re going to pass the guitar back and forth, and we’ll just play and sing whatever comes into our heads. We record it just in case we get anything good. And if we don’t, it doesn’t matter, does it? No one’ll hear but us.”

I looked at him with distrust. I knew that confidences promised didn’t always remain confidences. He’d told Jennifer Mills about my breakup with Susan Osmond the year before, even when I’d asked him not to. Over the summer, when Lex and Sonny Ford had been making fun of me, I’d then resorted to sharing Lex’s attempt to woo Jennifer Mills with a Lenny Kravitz song. “You know what this little bitch did,” I said, pointing to Lex. “He called her on the phone, all swooning…’You are the most beautiful thing, I’ve ever seen‘,” I warbled. And yet, I went along with his plan to record us signing improvised songs.

So we began. He pressed record and started to play. The chord progressions were standard. C-G-D. C-A minor-G. C-F-C-F-C-F-G. We weren’t breaking any new ground. We didn’t add any seventh chords, nothing diminished, the only minor chords we played were E and A minor. There were no guitar solos. And every once in a while, we broke into a cover, a sloppy rendition of “Blister in the Son” for example. After our initial trepidation, we loosened up and began showing off, not with guitar chops, but for comedic effect. We became, over the course of that evening, uninhibited, ridiculous, loopy. After he’d finished his first song, a song that’s faded in memory now (I thought I might still have the tape, but I’ve been unable to located it), he handed me the guitar and I took it with trepidation. Twenty minutes later, I was calling for it. As soon as he finished playing, I put out my hand.

“Here, give it to me,” I’d command.

I had a small Pignose amp my aunt had given me form her days playing guitar, and I saw it, and started to sing about a girl walking down the street, a girl who was beautiful but for one feature, and yet, that feature was the most alluring at all. “She had a pig nose!” I belted. “And it made me horny!” While Lex joined in from the background, “Horny! Horny!” (Perhaps it’s all for the best that this tape was lost). We rolled about, laughing. Of course, none of the songs we created that night ever amounted to anything. We never played them again. We didn’t develop them. But it got me loose. It got me thinking about writing. I could do it, I could make up riffs. The only thing was lyrics. They scared me. I wasn’t sure what to say. I wasn’t sure that I had anything to say, nothing important anyway.

I needed a reason to write. I needed something to write about.

What I needed was a muse.

There are no comments yet