I’ve fallen a bit behind in my Substack output here. Some of that is life circumstances, having to navigate buying a new car after our last one was killed in a flood at the end of August. More of it is that when I sit down to write, I do prioritize my creative writing over my Substack, which means the Substack only gets done if I have extra time, which I haven’t had much of in the past two weeks. Having reviewed all of Agnes Varda’s films via The Criterion Channel streaming service last month in my August of Agnes, I touched on some of the difficulties entailed in giving yourself an assignment to watch one artist’s films and reflect on them. You get distracted, you change moods, you want to watch something by a different director, the themes start to feel like a bit much when taken all in one gulp, but I also noted that overall, it’s a rewarding experience, so I figured why not do the same this month with Satyajit September in which I go a bit out of my wheelhouse and watch the films of the great Indian director Satyajit Ray.

About a decade ago, I watched the films available at that time on Criterion disc: The Apu Trilogy, The Music Room, The Big City, and Charulata, as they were available from the Philadelphia library, and since I discovered the Collection, I’ve been willing to watch pretty much whatever they put out, and I thought all those films were well worth my time back then and was interested, when I saw that there is a “Directed by Satyajit Ray” collection on the channel, similar to the Varda collection, in revisiting those films and taking in others. The caveat here is that unlike the Varda collection, the Ray collection is incomplete. There are a number of films not available on the site, and I haven’t done the due diligence to figure out if Criterion simply doesn’t have the rights to those or if, for some reason, the film elements are damaged or missing because they haven’t been preserved. Just yesterday, I watched the epic Three Sisters, which I’ll take about in a later entry, and clearly it has not undergone the types of restoration to clear up the natural aging of older films for an updated release. Will it? Honestly, I don’t know what goes into restoration or how long that would take or whether it’s performed if the company doing the restoration gauges there won’t be a lucrative enough reason to do it.

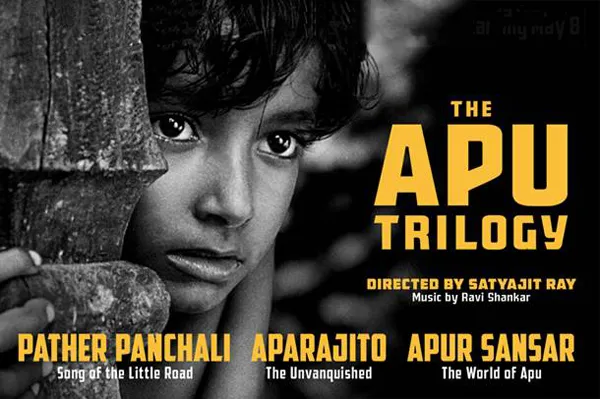

In any case, Ray started with some bangers straight out the gate with his Apu trilogy and The Music Room. The Apu trilogy consists of Pather Panchali, Aparajito, and Apu Sansar, all based on two beloved books by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, entitled (not surprisingly) Pather Panchali and Aparajito. The three films follow Apu from his birth into an impoverished family in rural Bengal through his coming of age to marriage and maturity, and it’s not an easy journey for him. In fact, over the course of the trilogy, Apu loses his elder sister in the first film, both his parents in the second, and his wife in the third film. You wouldn’t be blamed for comparing him to Job of the bible in the way he’s tested, and once his wife dies in childbirth, he abandons the child to her family and retreats into a monastic life for a time before the trilogy results in their reunification (fade to black). That’s a spoiler, I suppose, a spoiler on a 70-year-old movie, but then these aren’t really the kind of movies you watch hanging on the edge of your seat, engaged by the twists and turns of the plot. If anything, Satyajit Ray’s work reminds me of Yasujiro Ozu’s in the type of patience he exhibits, in the sometimes static camera work that focuses on characters engaged in mundane tasks.

Much of Pather Panchali focuses on Apu’s mother, and the kind of work she engages in to keep their small hut clean, to keep her family clothed, to keep them all fed. It isn’t an easy life for her, especially since her husband is something of a dreamer, an aspiring artist, who refuses to ask his employer for three months of back wages when they owe money themselves all over town. His father can make money off of his position as Brahmin priest, but he’s also unwilling to take advantage of other people in distress, and his good cheer makes us understand that despite his wife’s frustrations with him, there are many reasons why she loves him. In the meantime, Apu and his sister Durga roam about the countryside, playing with other children their own age in a way that seems, despite the poverty somewhat idyllic in its freedom. Durga often takes fruit that has fallen to the ground from a nearby orchard that their own family had to relinquish to neighbors as payment for a family debt, and is accused of stealing by such neighbors several times. Apu and Durga develop a close bond through these shared experiences, venturing out to see a train, dancing in the rain, but film culminates with Durga falling ill and passing away while their fathers is in the city looking for work. Having returned home to discover his daughter dead, they decide to move to Benaras to try their fortunes there. It is ultimately a heartbreaking film, and Criterion’s special features on the channel interview a handful of stars who were profoundly affected by the film including Karyn Kusama, who notes that it’s difficult for her to watch that ending without weeping, and Bill Hader who comments on the universality of the film.

I find the comment on universality both amusing and true. Amusing because most great art is universal in its specify. Watching the film, this is clearly an Indian work of art that comments on caste and religious beliefs unique to that part of the world while at the same time the family also endures the petty gossip of small towns, the striving to make ends meet and raise a family, the childhood experience of envying items other people have, such as when Durga steals another girl’s necklace because her family can’t afford such items. But that’s the whole appeal of watching films from around the world and the reason I wish more people would do it: it makes you understand that at heart we have many of the same needs desires, even if the cultural context and expectations around how those desires and needs are met differ in terms of the foundational stories we tell ourselves and the norms that society has established around employment and shelter and communal rights. In the same way that Agnes Varda really knocked it out of the park with her first feature La Pointe Courte, Ray does the same with Pather Panchali (they were released the same year, 1955). Panchali is an excellent film, even if Ray was young and inexperienced with the camera. It’s amazing when you consider that just how beautiful the film is (he wasn’t even a photographer like Varda was).

The follow up to Pather Panchali, Aparajito, picks up right where the first film left off, with the family living in Benares near the Ganges. Their circumstances are still impoverished, but the father has his hustle on, working as a priest officiating near the Ganges for religious ceremonies. The family seems to still be reeling from Durga’s death but recovering, and soon after the moves, Apu’s father takes ill and dies. The family returns to a small Bengali village, and while Apu is serving an apprenticeship as a priest, he convinces his mother to enroll him in a school and thrives as a pupil. It’s at this point that we transition actors from the young Apu to the teenage Apu, the boy now long and thin and gangly and in search of an identity in his education. He receives a scholarship to go to the city, but to do this, he must leave his mother behind, which understandably causes friction between them and serves as the core emotional story of the second part of this trilogy.

Apu, at this point, is your single-minded teenager with tunnel vision. He wants a future outside of the village life. He wants to explore what it is to be something other than a priest as his father was. He’s at the stage of life where he can’t possibly understand the difficulty his mother faces in letting him go, not only as he’s a source of income for the family (she’s found work as a maid as well), but because after losing her husband and daughter, Apu is all she has left. To be separate is, for her, excruciatingly painful. But she decides to let him go anyway. Not that life on scholarship is easy for Apu either. He struggles because to make ends meet he has to work at a printer press in the evenings, study afterward, and attend lessons in the daytime. All of this takes its toll on him, but because he’s young and hearty, he prevails, acclimating to city life and neglecting to write his mother or visit. She pines away for him, but retains her dignity and doesn’t let on how deeply hurt she is by this. She eventually falls ill and passes away without Apu realizing just how poor her health had become, and when he returns, he discovers he is now an orphan, having lost everyone that matters to him.

When we debate whether there have every been any truly great trilogies, the discussion tends to focus on action and sci-fi movies, Hollywood, the Western cannon. People might mention The Lord of the Rings or The Dark Knight trilogies, talk about how The Godfather fell off with Part III, but we always seem to neglect art film, foreign film and fail to mention, for example, Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colors Trilogy, and if that gets mentioned it seems people forget or are simply not equated with Ray’s Apu Trilogy, which might be the most complete trilogy ever made. The second film Aparajito isn’t my favorite by any stretch, mostly because I find it difficult to have empathy for that period of youth in the late-teens and early-twenties where the self becomes almost entirely narcissistically focused on its own needs, but the presentation of this period in Apu’s life is accurate and counterbalanced by the selflessness of his mother. And if there’s any argument to be had about this trilogy, I would assert that this is definitely one where the third and final film, Apur Sansar, may be the best in the series, which is often not true of trilogies (though I believe Red is the last of the Three Colors trilogy, and that’s my favorite there as well).

The actor who plays Apu is yet again recast here, Soumitra Chatterjee, or as I kept referring to him in my mind (or keep referring to him in my mind since he appears all over Ray’s filmography, as the Indian Diego Luna (tell me if you think I’m wrong; yes, Chatterjee was that handsome). We pick up here with Apu on the cusp of full maturity, temporarily working a tutor, while dreaming of becoming a writer. He still has a bit of the obnoxious teen in him, ducking his landlord and having dorm room-style philosophical bullshit sessions with his friend Pulu in the Calcutta streets at night, and he’s convinced of his own genius while at the same time unaware of his own charisma. Pulu invites him to his home village to attend his cousin Aparna’s wedding, but on the day her intended arrives, the family discovers that the boy she’d been arranged to marry has a mental disorder, and Aparna’s mother calls it off. Here, of course, is where our modern Western sensiblities encounter a situation we don’t entirely understand, but according to Hindu tradition (according to Wikipedia, yes I looked it up), the marriage must take place during an appointed hour and if it doesn’t, the bride is to remain unwed the rest of her life. So Apu is coaxed into becoming the bridegroom. Well, it finally seems that life is looking up for old Apu. His bride is from a good family, smart, capable and beautiful, and although they don’t know each other, they quickly bond in his small Calcutta apartment, falling in love over the course of their first weeks together. Aparna gets pregnant and returns home to have their child, and just when Satyajit Ray has coaxed us into forgetting that Apu is essentially the Indian version of Job, Aparna dies in childbirth.

The genius of the plot twist is that it’s both unexpected and entirely expected at one and the same time. The entire trilogy has prepared us for this. And yet, we’re so enamored of their love story, their chemistry is so intoxicating, that we can be forgiven for forgetting that Apu is a character from who everything seems to be taken in short order. Of course, this is true of all of us over a long enough time span. We are creatures that will eventually have everything stripped away, but seeing it in the timescale of six hours of screen time, as a reminder of the ephemerality of life, is devastating. Apu, naturally, is torn to shred by losing his wife, and he decides to leave and roam the countryside, ceding responsibility for his child to his wife’s family. If the film ended there, it would befit the tone Ray has set of Apu losing everything. It would make sense that Apu might never return, but we need a happy ending, so Pulu begins to search for Apu, only to find him working in a coal mine. He pleads with Apu to take responsibility for his son, and Apu agrees to visit the family home and see him. The child, in that village, runs a bit wild and most of the elders agree he needs a firmer hand than his grandparents can provide. Apu’s encounter with his son is awkward, and his son refuses to acknowledge that this is his father, yet when Apu turns to leave, his son chases him down in the road, and they reconcile. Apu finally accepting responsibility, and us, as the audience, glad the film ends there because if it continued who’s to say what might happen to the boy?

Out the gate, Satyajit Ray made a banger of a trilogy. Although I guess banger is the wrong word given how methodical the pacing is, the importance he places on letter small moments between characters play out to show us who they are and how significant these moments are between them. I’ve watched a half-dozen more of his films by now (as I’ve said, I’m falling behind in my writing) and he bears the hallmarks in this way of all the best filmmakers, at times reminding me of Ingmar Bergman in his focus on the interior lives of women or of David Lean filming Noel Coward chamber dramas like Brief Encounter. I’d like to catch up writing about them all this week if only for my own peace of mind because it’s often in writing about the films that they open themselves up to me more, that I can consolidate my thoughts into something resembling coherency, especially with all the distractions in the world today. I know this was a long one, but I had to choose between writing about all three films in the trilogy in one go or parceling them out, and I figured if I chose the latter, I might never get it done. So for the next few, I’ll try to narrow the scope to one or two movies at a time.

[mc4wp_form id=6322]