Coen Retrospective: Raising Arizona

Film Reviews // No Comments

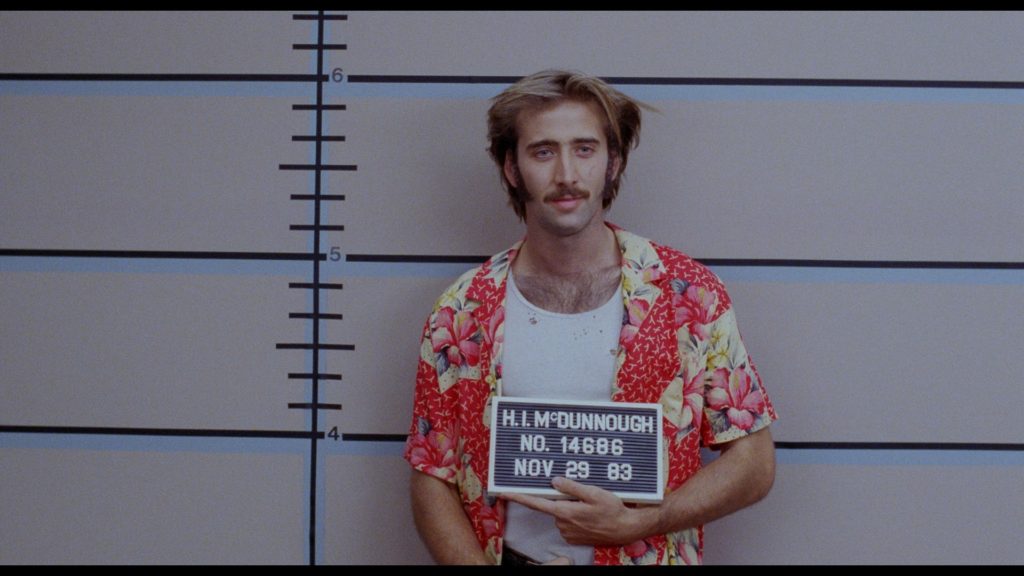

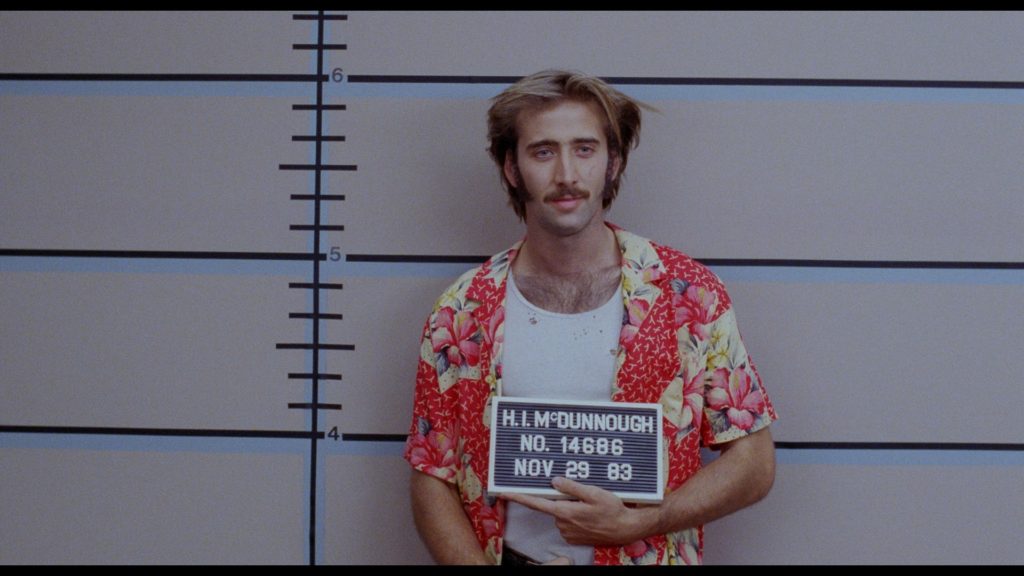

Until I sat down to watch Joel and Ethan Coen’s Raising Arizona last Saturday night, I hadn’t seen the film since I was a kid. I remember it being on HBO during my youth. I’m not sure how old I was, but I remember my dad laughing at some of the jokes. Some of the jokes I laughed at too, though being young, I was laughing because he was laughing. Not because I was in on it. The images I retained are those of Nicolas Cage with that weird hairstyle and conspicuous mustache getting his mugshot taken and John Goodman and his criminal sidekick leaving the baby on the roof of their car after a bank robbery. But watching, a great many scenes felt familiar. The prison break as rebirth scene. The bounty hunter on his bike, his jacket laden with hand-grenades.

We were still in the era of Reaganism when the Coen’s made Raising Arizona, and as such, the film can be viewed through the lens of questioning and critiquing certain values that were seen as fundamentally American at the time (and by and large still are). But unlike Blood Simple, which employed neo-noir to this end, the Coens use madcap screwball comedy to ask their questions here, and I say “ask their questions” because the Coens, in my estimation are never prescriptive or moralizing, but inquisitive. They give their characters a background, place them in situations, and see what happens.

At root, the film feels fresh, especially now in the climate of the 2016 presidential election. It looks at income inequality, the distance between haves and have-nots, resource allocation, and the ways in which denying access to opportunity results in criminal behavior and the cycle which leads to repeat offending and an endless cycle of the same people being processed by the criminal justice system. Which makes it all sound heavy, but it’s not. The movie’s a romping good time. The Coens are simply adept at throwing these elements under the surface of the plot, slipping in lines like, “I tried to stand up and fly straight but it wasn’t easy with that son of a bitch Reagan in the White House” without making it heavy-handed; a feat I’m not sure how they pull off.

The story begins with H.I. McDunnough, small time crook arrested for robbery (though unarmed, he makes clear, he didn’t want to hurt anyone), being processed by police. He meets police photographer Edwina and woos her through a series of meetings that involve him being released and arrested again for the same crime. Eventually, he gets out and they get married and want a family. But they discover Ed is infertile, and when adoption doesn’t work (“Biology and the prejudices of others conspired to keep us childless”), they decide to steal one of furniture tycoon Nathan Arizona’s Quintuplets. “They’ve got more than they can handle,” H.I. and Edwina use as justification.

Which brings us back to the land of capitalism, resource allocation. One way to look at their plight, being sterile and unable to adopt because of H.I.’s criminal past, is that he put himself in the hole by committing criminal acts. It’s never explained why he turned to robbery, though it’s implied there were absentee parents, and of course, we might say individuals make their own choices and create their own destinies, but is that entirely true? Nathan Arizona has done it. It’s noted he’s changed his name from Huffhiens to Arizona because “Would you shop at a store called Unpainted Huffheins?” And he’s built a fortune. But this doesn’t mean that such self-making is within everyone’s grasp.

“I don’t know how you come down on the whole incarceration question,” H.I. narrates, “whether it’s for rehabilitation or revenge, but I was beginning to think that revenge was the only argument that made any sense.” At least as far as H.I. is concerned, once that first mistake is made, you’re done for good. You have no choice but to retain the criminal lifestyle, repeat offense, parole board, back on the streets and rob again. Which happens. H.I. goes back to stealing.

They don’t just steal one of the Arizona children, but after H.I. loses his job because he won’t wife-swap with his boss, he robs a convenience store for Huggies. And what kind of world is it where you can lose your job for refusing to wife-swap? Well, it’s a world of cinema and comedy, but in a reality of at-will employment where your company can fire you for Tweeting views that are incommensurate with company policy on a private Twitter account, what we have in Raising Arizona is really just an amplified version of a company being able to terminate any employee for aspects of private life that have nothing to do with the ability to perform a particular job.

In the meantime, Nathan Arizona, furniture king, has offered a reward to anyone who can bring back his son. Cue the bounty hunter. If anything speaks to the time this film was made, it’s the representation of the bounty hunter, Leonard Smalls. He rides a Harley, smokes cigars, wields shotguns, and carries hand grenades. In short, he’s a pastiche of Rambo and the Terminator. He’s machismo incarnate. And he’ll stop at nothing to hunt down the Arizona boy, though whether he’ll bring him back for the reward or sell him on the black market is unclear.

“Price?” he responds to Nathan Arizona’s offer, “A fair price. That’s not what you say it is, and it’s not what I say it is…It’s what the market will bear. Now there’s people who’ll pay a lot more than $25,000 for a healthy baby. Why, I myself fetched $30,000 on the black market. And that was in 1954 dollars.” And ah, we’re back to unregulated capitalism/Reaganomics (in short, Republican economics) at their finest, bargaining over a baby. We’re also entering the zany realm in which people aren’t always at the controls of their own destiny, the implication being that this rugged road warrior (you can add Mad Max to Rambo and the Terminator as touchstones) has suffered at the hands of fate and part of the reason he’s become this unfeeling, calculated hunter is his upbringing (yes, the old nature/nurture debate). As we see in the climax, when Leonard Smalls chases H.I. to steal back the baby, they both have the same tattoo: a woodpecker. In typical Coen fashion, what this means is never stated overtly. Is it coincidence? Is it meant to imply they’re two sides of the same coin? Does it tells us that H.I. has a similar story as a black-market baby.

In any case, since this is a comedy, good prevails. H.I. defeats Smalls and saves Nathan Jr. They return the baby to his room in the night, and when Nathan Sr. finds them, they explain why they did what they did, and Nathan Sr. decides not to press charges. If you can’t have kids, he suggests, you just “keep trying and hope medical science catches up.” Raising Arizona ends with a dream. H.I. sees a future for himself and Ed, a future of old age and children and grandchildren, a happy home. And we’re satisfied that this is a happy ending, or the happiest we could have hoped for. But to me, there’s an underpinning of disquiet in that it’s a dream. Dreams are what we fall back on when we haven’t achieved. They may come true, and they may not. In the case of Raising Arizona, we’d like to believe it came true. But given the course of H.I. and Edwina’s lives so far, I wouldn’t put money on it. In America dreamers are a dime a dozen, and I hate to break it to you, but most of the time, they don’t come true.

There are no comments yet