“We should have hit the bar scene,” Lex says. “We should have hit that scene, and we never did.”

We’re back at Jim Lyon’s wedding now, talking about why our band had never panned out, why Coldplay had somehow become the biggest rock act in the world instead of us. This was a part of that conversation, why our talent never led to greater things; why our talent could just dissolve like that (because we had been talented we insisted); why we’d never made it to making an album, playing more shows; why the band hadn’t lasted past college and Lex’s move to New York. To him, it was all because we didn’t make the right moves, didn’t follow the guidebook closely enough. For him there was a guidebook. At least in retrospect. I’ve never been one for guides, paint by numbers paths to the stars, algorithms that predict success. I have to disagree.

“I don’t think that’s it,” I say. “I think you and I were too close, and we never let anyone else in. There was Pete for a while, we would have let him in, but he had his own thing. Gabe was serviceable and I liked him a lot but he was never in it for the long haul. The fact was, you and I had trouble letting people into our thing. We never found the musicians who could play with us. Or not just with us, but who could contribute something substantial to the sound.”

Maybe the truth is somewhere in between, as most truths are. Why didn’t we try to play other shows? I mean, yes, we were a two piece, and there weren’t many two-piece models in rock pre-White Stripes. We weren’t entirely certain how to exist without a bassist, but we played some good songs, just the two of us. A cover of “Tales of Brave Ulysses.” A strangely complex, and yet hypnotic and beautiful, song I’d written on my Rickenbacker twelve string called “Skyline Drive” for which no recording exists. We jammed together the next four years, just the two of us, but we never thought to take it out of his basement and onto the stage. There was a bar scene. Maybe we could have called Pete and opened for his band. But I didn’t have the confidence to go up, just me and Lex. I was content with recording demos, but most of the songs I was not writing were hard to get down on tape because of tempo changes and ornate structures. I was getting bored with verse-chorus-verse. So we ended up recording bits and pieces, riffs with potential. Lex learned to paint, and I learned to write.

I’ve started to get away from scenes in the past few sections because they felt too fabricated, all my past is too far away, my memory not as keen as it once was, and yet I’ve returned to one here because this was only August, and still, it has a made-up feel. We said something like this, if not these exact words. We spoke of a break between us. We spoke of why it happened, but as we stood, talking, I realized a break had never occurred, not really. There was never a point at which he or I had said to the other that we never wanted to see or speak to each other again. In fact, I’d always been able to get ahold of him if I really needed to. His number has been stored in my phone all these years.

On the morning I found out Rick had been shot in Old City, I made the rounds and called everyone. I hadn’t spoken to Lex in almost three years, but I left a message and he called me right back. We didn’t call each other to shoot the shit, those days were past, but if something was important, I could reach him. And so Rick died, and we had gathered at the William R. May Funeral Home to say goodbye to our old friend, a friend we’d drifted away from around my junior year of college. We had drifted away from Sonny Ford earlier than this. Before I left for Rome, we’d set a distance. Part of it was that Sonny was having problems that we couldn’t solve for him. Part of it was that we knew that Lex and I and Jim would end up leaving Glenside while Rick and Sonny would stay behind. But Rick hadn’t stayed behind. While Lex and Jim had moved to New York, I’d moved to Philly, and Rick had too. We weren’t connected any more and I’d see him around, but we’d ignore each other. The last time I saw him we were both at the bar National Mechanics. He was two tables away and I spotted him. He had new friends, he was laughing. I had new friends too.

One morning, not long after, I got a call from my mom.

“Rick’s been shot,” she told me.

It was early morning, a little after six a.m. I live in dread of calls at that time. It’s never good news.

“What?” I was still shaking the sleep from my eyes. “Was he at shooting range? Was he playing with it?”

Rick was clumsy but good-natured. My first thought was, of course, that he’d shot himself, that it was an accident.

“I don’t know what happened. They found him in his apartment. He was with friends, and they ordered a pizza, and after a while they left, and someone shot him in the head. His roommate came home and found him. His mom’s at the hospital now. They took him to Jefferson. Can you go and see her? She’s all alone.”

I went to my room and got dressed and told Kristine what had happened. Rick was an old friend of mine, and his mom was a friend of our family. She’d been there for us all over the years. She’d tutored us all in math. She read my papers for school, my stories. Of course, I wanted to be there.

“I’ve got to go,” I said.

We lived in South Philly, and I half-ran, half-jogged down tenth street to Jefferson. When I got there and told him who I was there to see, a cop came over and asked a few questions, but when it was clear I didn’t know anything about what had happened and wasn’t there to finish the job, he left me alone. Rick’s mom came down and met me in a small cafeteria on the mezzanine. She was shook up.

“I don’t think they’ll let you up to see him,” she told me. “There’s a cop stationed at the door. Besides, you wouldn’t recognize him. His head’s all wrapped in bandages.”

I had gone there thinking that there was something I could do, but there wasn’t. The call that woke me was unexpected, unreal. Rick had been shot. I’d assumed that maybe he just winged himself. That he was going to be all right. Even after my mom told me what happened, I still didn’t believe it. But here, the reality set in: he was going to die. She told me she’d called his dad in Texas, they were planning to take him off life support later that afternoon. He was already technically gone.

“I have to get back,” she said. I got up and left. It was a brisk gray November morning. I pulled out my phone and started to call around. First was Jim.

Jim was the only guy from the group of friends I’d grown up with that I still talked to on a regular basis, even though he was the last guy we’d become friends with and the last that any of us had wanted to become friends with. We had seen him at first as a pest. He was in the grade below us. He was nearly two years younger than Lex and six months younger than me. He was a slender kid, who started to show up at Sonny Ford’s house in the summer between our junior and senior years of high school. He lived down the street from Lex, so we’d seen him around, but I’m not sure who invited him over. He’d drive down Paxon Ave. in his blue and white Bronco, and we’d see him coming and clear out. We’d go somewhere else and he’d follow. But he wanted to be an artist, and he sensed this in Lex and me, and he glommed onto it. Or maybe it was a weed smoking thing, since he and Lex didn’t start painting seriously until much later. In any case, he was a persistent son of a bitch. We made fun of him. Tony P., whenever Tony P. came around, called him Ethy because of how skinny he was. And still, he kept coming. And as Drew Schiff and Tony drifted away from the group and made new connections, developed new interests, found new lives, Jim became a fixture. In fact, Jim moved to New York with Lex when the opportunity arose–there’d been a spot for me, but I declined–and he’d been living there ever since. When Lex got married, Jim had moved to Jersey City which is where he lived now. He picked up after a few rings.

“Jim, I got some bad news,” I said. “Rick was shot.”

There was a moment of silence.

“Was he playing with a gun or something?” Jim asked.

It made me feel like less of a dick that this was his first thought too. That our minds didn’t instantly go to murder was more the result of the fact that people we knew didn’t get murdered. Rick had always been clumsy, so our thoughts went there. That was the first thing. The next, of course, was that Rick had money, the result of some vague lawsuit from when he was young. Could it be robbery gone wrong? Then there was drugs. Rick was a pothead. But when we’d known him he wasn’t above dabbling with harder stuff. This was all floating out there, unsaid. In the coming days, he’d call me back and we’d kicked around ideas. Why had it happened? What had been going on in Rick’s life that led to this? We’d all fallen out of touch with him, so we could only conjecture. The police had no leads. How does someone not hear a gunshot in Old City on a Friday night? I wondered, again and again. Was it a hit? Had someone used a silencer? I didn’t know the first thing about firearms. Maybe the people there thought it was firecrackers. I didn’t know how to feel. I hadn’t much liked Rick in our final years as friends, and yet, no one deserved what had happened to him.

He was my first friend in that group. He’d wandered up to me on Keswick Avenue shortly after he and his mother had moved to Glenside. We were just about to enter the second grade, and he’d asked me to play with him. Just like that: “Do you want to play with me?” There was no guile in him at that point. Nothing of the future irresponsibility I’d become so critical of as we entered our twenties and he fathered two children with a teenage girl whom he then proceeded to care for only monetarily. I’d been hard on him. I’d turned my back on him because he didn’t acknowledge them. I was betting the friends who knew him in those final years weren’t even aware that he had any kids. It wasn’t as if we were living in an age where his lack of recognition would mar their social status in any way, but still, he was absent. It had rankled, but I felt like all was forgiven now. All had to be forgiven. Only a fool would hold his grudge against the dead. And still, he came to me in my sleep. I woke one night after a dream of him and opened my eyes and he was standing there, a ghostly image that faded away as I came back to full consciousness. We had always been kind of jerks toward Rick. We’d made him our jester, our fool. And I spent the weeks after his death wondering whether things would have been different if we’d been better friends to him; if I’d been a better friend.

The next person I called was Lex, and I left a message and he called me back.

“Let me know when the service is,” he said, after I’d told him the details I knew.

The last person I had to call was Sonny, and that was the hardest to make. Sonny, from what I’d gathered, was still living with his parents. I remembered the number there, even though I hadn’t dialed it in years. While I’d felt no guilt in turning my back on Rick, I thought of Sonny often, of how we’d left things.

We had abandoned Sonny. There’s no other way to put it. Every one of us. Rick, Jim, me and Lex. It happened the summer before I went to Rome, my junior year of college. We’d convinced ourselves that the decision we’d come to was good for him, but the ease with which we’d arrived at this decision proved only that it was good for us. I had a girlfriend then, my second in college, and that’s what it started, with the end of our relationship. This was the girl who disappeared, the one who’d left in a frenzied state the night in question, a night for which I’d purchased tickets for us to see Orpheus Descending at the Wilma Theater. And I wanted to find someone who could use them.

This was pre-cell phone, so I had to call round to houses. I called Lex first but he wasn’t home, and then I tried Jim. They were out together downtown, his mother informed me. I hung up and called Sonny. He was in his room, “Nah, man, I’m cool,” he said. “I’m just gonna chill here.” His room was where we always hung out when we had nothing to do. “But your just gonna sit around and smoke pot,” I thought. But I was never one to push, not like Lex. I called Rick, but he wasn’t home either. So I thought to page Jim. His parents had bought him one of those little pagers you could clip on your pants. I’d dial the number, and mine would show up on a screen on top, and he’d call me back if he felt like it.

A few minutes later, the phone rang. “What’s up?”

I told him what had happened.

“We’re downtown now, want to come meet us?” I did.

I didn’t know what happened. I couldn’t explain it. All I knew was that I didn’t want to be alone. I had a trailpass, which I used to take the train to and from school, and it also took me into town. I hopped on the next and rode into the city to meet them. I told them I’d be out front of the Wilma Theater. I asked if he and Lex wanted to use the tickets. I didn’t have to see the play myself, but I didn’t want them to go to waste. But Lex and Jim declined. It was a nice summer night. They didn’t want to be inside. I spotted two kids about my age who were sitting atop the marble slab above the Walnut-Locust subway stop entrance.

“Hey, you guys want tickets to the play?”

They looked like University of the Arts students. One of them, the guy, wore a fedora. He looked kind of like Duckie from Pretty in Pink. The hipster style of the late nineties. The other was a girl with her hair dyed pink. They looked at me like I was running a con.

“Really?” the guy said.

“Yeah, it’s not a trick. Broke up with my girl. Well, maybe broke up. In any case, I can’t use them. But I don’t want them going to waste.” I saw Lex and Jim turn the corner on Spruce. I handed the students the tickets.

“Enjoy.”

“You want money for them?”

“No, my treat.”

Lex and Jim waited for me next to the subway stairs.

“What happened?” Lex asked.

I was embarrassed and didn’t want to say.

“Come on,” Lex said. “How long have we known each other now?”

He had a point. He knew almost everything about me.

“Well, we were gonna go to the show. But we had some time to kill beforehand. And no one was home…so, I went down on her.”

“Okay, then what happened?” Lex said.

“Well, when I finished, we were sort of sitting there, and I thought, I’ve been doing this for her, maybe it would be nice if she did it for me. So I asked her, ‘Would you do me?'”

Jim interjected, “Wait is that how you said it? Did you really say, ‘Would you do me?'”

Lex waved him off.”So what? It doesn’t seem unreasonable to ask her for reciprocation after you just did it for her? I mean that’s part of a relationship.”

“I don’t know what happened,” I said. “The words were hardly out of my mouth, and she just started freaking out.”

“You didn’t…insist, right?”

“God, no! Who do you think I am? I just asked.”

“And that’s really how you asked?” Jim said. “‘Would you do me?'”

He started laughing.

“Oh, go fuck yourself, Jim. How would you ask? Oh, that’s right. You don’t have that problem. Because you don’t have a girl.”

“At least I’ve had sex.”

“Yeah, twice, you big stud.”

“‘Would you do me?'” he said. He kept laughing. I had to laugh too. He was right. It wasn’t exactly cool or smooth. And I could either be terribly embarrassed or recognize that there was humor in it.

Lex kept us on topic though, “And she didn’t say anything as she left. She didn’t even try to explain why she was upset?”

“Why? What are you thinking?”

“Well, I think you need to talk to her,” Lex said, “once she’s calmed down, and figure out what happened. But I don’t think you’ve got long in this relationship.”

“You think she’s breaking up with me for this?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think so. But I think that all the sex stuff has been one-way. You do things for her, and she won’t do them back. And if you’re okay with that, it’s cool. But it sounds like you want certain things that she’s not going to be able to offer, and you just can’t go on like that. Resentments build up. Even if you try to act like you’re okay with it.”

“So what do I do?”

“You wait. It’s her move. Either she calls to explain what happened or she doesn’t.”

It’s been over fifteen years since that night, and in that time, I’ve learned there isn’t really a smooth way to make the request I made. Either your partner reciprocates in the heat of the moment or they don’t. This doesn’t mean that I haven’t on occasion asked, and asking, on occasion, does meet with success. But I was so inexperienced then, I worried that I had done something wrong. I hadn’t expected her reaction. “No, I don’t want to,” seemed a reasonable response. But to stand up and storm out, this left me utterly shaken and profoundly confused. I had asked harboring the naive impression that maybe reciprocation hadn’t occurred to her. That maybe she didn’t think that I wanted it. Or maybe she was scared to initiate it, and if I just let her know it was okay, then she’d do it. She was only a little more experienced than I was. So I said, “Would you do me?” And now I was in the city, with my friends, walking around aimlessly. Eventually, we found our way to Tower Records on 7th and South Street where I bought a few CDs. This always made me feel better.

I didn’t know what I’d do. How I’d wait. I didn’t want to break up with her. I didn’t want her to break up with me. I wanted to talk and work through it. I didn’t like what Lex had said. We could work through things, that’s what couples do. And yet, it wasn’t really working. My girlfriend and I hardly had anything to talk about. Usually, we hung out in my room and watched a movie and made out. We’d go to the movies or drive around. But we didn’t talk. I simply refused to recognize it. I was in a phase of wanting every relationship I was in to work out, to last. Because I didn’t have any girlfriends in high school, I assumed that girls didn’t like me, so if I got one, if one agreed to date me, I should do my best to hold onto her. Because who knew when the next would arrive, when that anomaly would occur and one would take an interest in awkward, gangly, frizzy-haired me.

We piled into Jim’s Bronco to head back to the suburbs. I briefed them on how I’d tried to give the tickets to Sonny and then Rick and no one would accept.

“Dude, that’s fucked,” Lex said. “You know that Sonny’s got nothing better to do tonight. He probably skipped it to smoke pot in his room and watch the Phillies game.”

“Well, he’s at Rick’s now,” Jim told me. “They’re probably sitting around and playing Play Station or something.”

We decided to head over there. We had nothing else to do. When we arrived we found Sonny and Rick in Rick’s room, slumped across Rick’s mattress, glassy-eyed and playing Play Station, just like we’d expected. There was music coming from Rick’s stereo. But I figured it was just something random, so I unwrapped my CDs and put one in.

“Dude, what the fuck?” Sonny said. “I was listening to that. That was my new mix.”

Among me and my friends, making mixtapes was a competitive act. We’d try to impress and outdo each other by blending similar sounding songs together, by crafting a mood using other people’s poetry. It was pretty firmly established that I made the best mixes. But there were always pretenders to the crown. And I recognized that Sonny had made this mix in hopes of impressing us, and maybe me most of all. But in that moment, I didn’t much care. I popped my CD out of the player, put his mix back on, and said, “All right. I’m not feeling this now. I’m gonna go.”

I walked out into the night and turned left and started walking toward Easton Road. This was me at my most content, walking, letting my thoughts swirl around. And yet, I wasn’t content. But it wasn’t Sonny or the mixtape that bothered me. I didn’t mean to insult Sonny by turning off his tape, and I wasn’t angered by his reaction. I wasn’t even that hurt that he didn’t decide to take the extra ticket and come with me to see the play. I simply didn’t want have the same discussions/arguments we had every night in Rick’s room or Sonny’s room. I didn’t want to sit there in the bong haze of that dark and depressing room, the blue glow of TV painting our zoned out faces, getting a contact high. I wanted time to think.

Had I done something wrong? Should I apologize to her for asking? Was it wrong to have asked? Men and women in relationship did these things for each other, right? I didn’t want to be an asshole, but I wanted to share these things with someone. Lex was right in that. I liked doing things to make her happy, but I wanted things for me too. And part of my asking was born of the feeling she’d forgotten about me. We’d been together six months. In that time, I’d learned how to get her off. She even sometimes pushed my head down lightly and thrust her hips up rather than ask to indicate she wanted me to do it. But I rarely got there myself. Was I being a typical guy? Was I thinking in terms of duration should equate with acts? Should I have changed my thinking, been patient. I kept telling myself, We’ll get there. She just has to feel comfortable. And I kept waiting, and finally, I’d asked for what I wanted. I didn’t think I’d applied any emotional pressure. I had tried to ask as benevolently as possible. But maybe the pressure was just there, born of the fact she knew the question would come at some point, arising out of the truth that she wasn’t ready and knew it and knew that if she couldn’t deliver, I might be disappointed, and she wouldn’t want to disappoint me because she did like me. But this was all conjecture. Until we talked, I wouldn’t know for sure. Was this going to happen every time, with every girl? Would there even be another girl? A next time around? And when did everything start to become so complicated?

After I’d gone a few blocks, I turned around and saw Jim and Lex jogging to catch up with me.

“What’s going on?” I said.

“Nothing,” said Lex, “I just thought it was fucked up that Sonny acted like that. He knows what happened, right?”

“Well, he knows I had a fight with my girl. But he doesn’t know everything.”

We’d reached the corner of Easton and Keswick where the 7-Eleven was and turned left.

“I still can’t believe he wouldn’t go with you,” Lex said. “He wasted those tickets. He would have had a good time too.”

“It’s not that important to me, Lex.”

“No, man. It’s not cool. Did you see them in there, laying around stoned? I mean, he couldn’t go to a play with you? One night of his life? When your girl walked out?”

“Dude, it’s all right.”

I couldn’t understand right then why his focus was Sonny. I’m still not sure at a fifteen year remove why he chose this line. Did he know he planned to do when he left me? Am I ascribing too much forethought to Lex? That’s highly likely. He was bright, and he understood people. He could read their weaknesses, understand motives. And maybe he wanted things to end as they did. Maybe he was looking for a reason to push Sonny out. But I’m not sure why, not right then. I think all three of us, Jim, Lex, and I, understood that we wouldn’t be friends with Rick and Sonny forever. That at some point a separation would occur. We were already talking about moving to New York after I graduated, and we knew that Sonny and Rick weren’t coming with us. But that was two years away. Jim was heading off to travel with the theater troupe, Up With People. I was going to Rome at summer’s end. If Lex lost Sonny and Rick now, he’d have no one. He’d be alone. So I can’t believe he went back to Rick’s with the intention of setting in motion a chain of events that led to us boxing Sonny out, turning our backs on him. But that’s what happened.

“I’m gonna say something,” he told us. And he turned and went back to Rick’s.

“What’s got up his ass,” Jim said. And we both kept walking. We circled around back to Keswick and Jim left me at my parents’ door.

“You’re gonna be all right,” he told me.

“Yeah. Yeah, I’ll be fine.”

I walked inside, wondering if she’d called. My parents were sleeping. But there was a note on the whiteboard in the kitchen that she had. I picked up the cordless phone and called her back. She picked up after two rings. She had a private line in her room. She must have been waiting for me to call.

“Are you all right?” I said.

She was quiet.

“There’s something I have to tell you. A reason I acted that way, and it doesn’t have to do with you.”

I waited and held my breath. I didn’t want to make a noise as she worked up the courage to tell me. Looking back, it feels like I knew. Or should have known. But I didn’t know. I couldn’t have known. If I’d known, I wouldn’t have been so glib about it with my friends. I probably wouldn’t have told them at all. Things like that didn’t happen to the people I knew. But of course, things like that always happen to the people we know. “I have a cousin who used to babysit me…” she said.

I sat listening, but right as she started to tell me, I heard a knock on the door. I was sitting on the sofa in the living room. From there, whoever was knocking could see me. I tried to ignore it, but the knocking became insistent. “Jay,” I heard Jim say, “Jason, open up. It’s important.” I sat and watched his outline at the curtain. “Jay, come on, we need you now. Open up.”

Her story hung by a thread. I knew it was hard to open up, so I didn’t stop her. Instead, I opened up the front door and held up a hand. I took the receiver away from my lips and mouthed, “Not really a good time…”

I waved Jim away. But he stood his ground.

“Sonny slit his wrists,” he said. “We’re not sure how bad. He only showed Lex. He showed him his wrists and the knife he used and the knife was covered with blood. He’s at the courts right now. He’s screaming and bashing his head against the blacktop.”

“Fuck my life,” I hissed.

I put my lips back to the phone and held a finger up for Jim. “I’ll be right with you,” I told him. “I just…I have to handle this first.” My thoughts were with her and with him. She’d been hurt years ago, in a way that had she hadn’t reckoned with, in a way that might have been irreversible. She was trying to tell me about it. Meanwhile, in the night, my friend was hurting himself. He’d hurt for years too. Both were hurts that happened beneath the surface, hurts they kept closed up until now when both were revealed at the same time, and I didn’t know what to do. They both needed me. I had a feeling if I got off the phone prematurely I’d never hear from her again. Yet, I had a feeling too that if I didn’t race to Sonny, if I didn’t help when he was crying out, I wouldn’t forgive myself. So I waited for her to finish telling me. I stood on my porch in stocking feet, staring down toward Renninger field, and I listened and waited, my stomach bound tight within the fabric of my throat. I felt responsible for everyone, for her and for him. And I didn’t know what to do. There was silence again. She had finished.

“I’m so sorry,” I said. “I’m sorry that happened to you. I’m sorry if you felt any pressure today. I understand.”

I meant it, but it sounded disingenuous. I was thinking of Sonny too. My attention was divided, my heart in two places at once. And I wasn’t equipped to deal with either situation. I sensed my own ineptitude. I was woefully out of my depth. I wasn’t close with Sonny. Lex was closer. Rick was closer. Jim was closer. But I’d always liked Sonny. I wondered what Lex had said to set him off. Had he really slit his wrists? Was it a cry for help? How serious was it? I couldn’t tell until I got there. But I couldn’t leave this as it was. We were silent again. I kept searching for words to let her know she’d gotten through, that we could work our way through this. But she said, “I think I need to be by myself now. I’m not sure this relationship is working for me.”

I didn’t want that at all. It wasn’t the result I was looking for, but I didn’t know what to say to convince her otherwise. I’m not sure I entirely understood the weight of what she’d just revealed.

“Maybe we can talk tomorrow? I mean, it’s cool, we can back off and cool it. Maybe just be friends for a bit. But you might feel different in the morning? But we can be friends.”

“Sure,” she told me, “maybe.” And then we hung up. I’m not sure if I knew then but I suspected that our relationship was over. There was too much contained within those few hours to get past, to continue. We talked a few more times in the coming week, but never saw each other again, and when I got back from Rome, she was gone. I couldn’t find her on campus. She’d just simply vanished.

I placed the phone on the porch and dashed off down the street. I could hear him howling from a hundred yards away.

“I’m no good! I’m a bad friend! I’m no good!”

I turned down Parkside Avenue and reached the courts. Though it was midsummer, Sonny was wearing an oversized sweater. He’d pulled the cuffs of the sleeves over his wrists.

“I’m no good!”

Sonny had a hard life. We all knew about it. His older brother had been a funny popular guy who Sonny had looked up to, but when his brother was in his late-teens he’d started showing signs of mental illness and been diagnosed as schizophrenic. Though his parents were still married, I hadn’t seen them speak more than a few sentences to one another in the entire time I’d known him. Usually, his mother holed up in the bedroom, chain-smoking and watching daytime TV, talk shows, soap operas while his father ran around the neighborhood. Running and running as though to forget their troubles. Sonny himself had learning disabilities and was dumped in a school that didn’t do much for him, despite the fact that he was bright, cunning, street-smart. His mind was sharp. He understood emotions easily, quickly. He was perhaps the most sensitive of the five of us. He had a good heart, he was a loyal friend. And here he was, lying on the ground, banging his head against the cement, swearing that he was no good.

I asked Lex what he’d said. I was standing there in socks. After I’d hung up the phone, I hadn’t thought to put shoes on.

“I just told him it was messed up he didn’t go with you.”

It sounded benign but I knew the way that Lex could make you feel. Low. Ashamed of yourself.

I knelt next to Sonny.

“It’s okay,” I said. “You didn’t do anything wrong. I’m not mad at you.”

But my words had no effect. The only one who had an effect was Lex. The only one whose words meant anything. Part of my distance from him was that he couldn’t offer me much. Or, he could, but what he could offer was offset by his house, the life around him, which frightened me. It was divided by his brother’s illness, sinking, most of all, depressing to be in. And since I was hardly strong enough to believe fully that I’d ever really make it out of Glenside, which was all I wanted, I certainly didn’t think I’d be able to pull him with me. And this meant letting him go at some point. In this way, I can’t escape the bald truth that Lex and I were alike. Whatever I couldn’t deal with emotionally had to fall by the wayside. But not like this. I didn’t want it to be like this.

“What do we do,” I said.

Jim and Rick just stood there, staring. Lex shrugged.

“The cops are gonna come soon,” I said. “They’re gonna haul him off and throw him in a holding cell. That’s the last thing he needs. Help me get him up.”

But it was too late. I looked up across Renninger Field and saw a squad car cruising down Keswick. It turned onto Parkside. It flashed its lights, one loud blip and Sonny was up and out of our hands. He dashed across the courts and down the stairs and into the woods behind them. For a big guy, Sonny was swift and agile. He knew the woods back there, and if given chase, the cops would have a tough time catching him.

“What do we tell them?” I said. “Did he slit his wrists? Do you think it’s bad? I don’t think it’s too bad. He couldn’t run like that if it was.”

“I don’t know,” Lex offered. “All I know is if we tell the cops he slit his wrists they’re gonna take him to the psych ward. And with his brother being like he is, that’s probably the worst thing for him right now.”

We stood our ground as the squad car pulled up. Lex did all the talking.

“Our friend’s a little drunk and upset, officer. He’s having a rough night.”

“Well, we’re going to have to find him and talk to him,” the officer said. In the meantime, two other squad cars had rolled past on Keswick. One had turned up Waverly Road, past the playground on the other side of the creek. I could see it shining its spotlight into the woods, the beam waving about over the swings set and sliding boards.

“If we see him we’ll try to stop him,” Rick said. It was typical Rick, his tone at once deferential and snide, irreverent and brown-nosing. I never understood how he struck that balance, and only he could do it. But the officer’s stare lingered on him. For as much as I found the tone Rick struck fascinating, it was also dumb. It drew attention and I would have thought the last thing Rick wanted, with all his drug paraphernalia, was attention.

The officer’s gaze lingered but left him. He turned and went back to his car and drove to join the search. Our group convened and walked across the field, back toward Rick’s. It was out of our hands. Our friend’s fate was his own. Still, the question lingered: should we tell them about his wrists. I was convinced by this point that if he’d cut himself, it wasn’t deep. My opinion remained it might be better to keep it to ourselves. But as time wore on and the squad cars circled the block, Lex changed his mind. Part of this was that he’d called his mom, who was a nurse. We had to give the cops all the facts, she said. They couldn’t help Sonny if we weren’t up front. The best option for him was probably the psych ward, she said. So the next time a squad car passed, we flagged it down.

“He might have cut his wrists,” we said.

Jim had gone out to look for him, as had Rick while Lex and I waited, back at Rick’s house. Our eyes scanned the field. There were woods behind the houses on Parkside as well, a dirt driveway that ran the length of the street, a row of rundown garages. And then we spotted Jim emerging from there. We ran over to meet him.

“They got him,” Jim said. “Over near Brookdale. It took three cops to wrestle him down.”

One of the cops came by to tell us what happened.

“We’re taking him to the drunk tank,” he said.

We were irate.

“What? But he cut his wrists. Doesn’t he need to go to the hospital?”

“I hate to break it to you, boys. But it was ketchup. It was all over his sleeves. And if he didn’t really cut himself, there’s nothing we can do.”

No one was angrier than Lex. Sonny had shown him his wrists. He’d shown him the knife, and it had all been fake. A cry for help, Sonny was desperate, we all acknowledged that. But it hadn’t been real. We broke it up and went home. It was late and there was nothing left to do. We weren’t going to drive to the station and bail him out or protest. The cop told us he’d be released after he slept it off. And the next day, Lex called us all together. He’d gathered materials, pamphlets.

“Sonny needs help,” he told us. “It’s help we can’t give him. I think we’re only enabling him by hanging out. He stays in his room all the time and drinks and smokes pot. And we come to his house and hang out and do it with him. And it’s got to stop. He’s falling further and further into depression. I have information on counselors and insurance we can give him, but I think that we need to create some distance.”

We all agreed. I didn’t take much convincing myself. I hate to admit it, but I knew that if the break had to happen between us, this was the cleanest way to make it. We could, of course, allow some drift to occur, stop showing up to hang out, let things take their course. But it seemed best to first rally around Sonny and suggest that he get help. It was then up to him to take our advice or leave it. But it still felt underhanded. As much as I was for the plan, there was an ache. It felt so much like betrayal. If we wanted to help him, then why didn’t Rick stop smoking and drinking, or Lex? Why didn’t we stop spending all our time confined to two bedrooms, playing video games every night? Why didn’t we get out? We had a whole city at our disposal. It wasn’t New York, but Philly was great in its own right. I had tried it. Tickets to the theater. That plan had backfired, but it wouldn’t every time. And there were the Ritz movie houses. We could go see films. Not blockbusters, but art movies. We could broaden our reach, expand our minds that way. Of course, this was my plan. I’d already started to break out on my own. I’d made friends in college. I was spending more and more time in the city. I’d started a book club with a guy in my Intellectual Heritage class, and we met downtown. The friends I made there would end up being the friends I lived with once I graduated and decided not to move to New York. I was taking small steps, but I was heading the direction I wanted. Still, Rome was complicating things. I was leaving, so I couldn’t say, “Why don’t we do it this way?” Because I would be gone. The decision we made now affected Sonny. It affected Lex and Rick. It had nothing to do with me. It had little to do with Jim. So we offered up no protest.

We marched into his room and told him he needed help and we couldn’t keep doing the same things we were doing. We couldn’t keep hanging out. If he needed support or help, he could call us. But we’d no longer be in his life every day. The words sounded hollow to me then, as they do now. As promises do, when I know in the back of my mind I have no intention of keeping them. I wasn’t going to be there. I was going to be as far away as possible. I wanted to mean it, and I somehow convinced myself I did. But I knew that I didn’t.

I’d like to say it haunted me, but it didn’t. Or it haunted me only when I saw him, which I did from time-to-time, home from the city for Christmas or Thanksgiving, at a local bar. We greeted each other with affection, old friends. He’d smile and shake my hand. But underneath it all was this, the lingering betrayal, the subject we did our best to avoid, the one we danced around while we played nice. Because Sonny was nice and wouldn’t bring it up, even though I knew it hurt him. And I might have brought it up, if only to apologize, though even my apology was meaningless. We couldn’t go back. I couldn’t undo what we’d done, nor did I want to. I’d made my life and liked it. There wasn’t a place for Sonny or Rick. And Lex had disappeared too. And all I had from that time in my life was Jim. And I thought of all this, as I stood on the street and dialed the number to let Sonny know that Rick was going to die.

He thought I was joking. As if, after all these years, I would call him and make this up and be that cruel. But I suppose thinking it was a joke was better than thinking it was true.

“I wouldn’t do that to you, Sonny. You know that,” I said. “I’m so sorry to have to tell you this way.”

Rick’s funeral service was the first time Sonny and Jim and Lex and I had all been together in the same room at the same time in nearly a decade. We were cordial to each other and fell into old roles. Lex had come with his wife. They’d been married for maybe two years. They’d been married in Central Park in a small ceremony, and of our old group, only Jim had been in attendance. His wife was someone Jim had met traveling with Up With People, and he introduced her to Lex. Kristine and I were living together but not married yet. It was the middle of the week and she’d had work and I told her not to take off for this. She didn’t have the personal time to spare, and besides, she’d never met Rick, and though I mourned the loss–this, despite the fact, we’d fallen out–I didn’t need her support. I figured it was best if I saw Lex and Sonny alone. Jim, of course, I was still in regular contact with, and he met me at my parents’ house for the walk up the street to the funeral parlor. My parents were going too, since they were friends of Rick’s mom. His dad had flown in from Texas, and I held my tongue, but he was just as full of shit as ever (after the funeral, he’d start badgering Rick’s mom for some of the money from an old lawsuit that had provided Rick’s income; money that should have rightfully gone to Rick’s children). He gave some contrived speech about his son being a “golden boy,” which I guess played to the masses (honestly when I think of him I’m still not sure how that man can look at himself in the mirror every morning except of course that people often can convince themselves of their own bullshit; it’s possible I’ve been doing this the whole time in this memoir, though I’ve never tried to milk a couple kids out of their inheritance), but it didn’t play to us, the old friends, the ones who had known him since childhood.

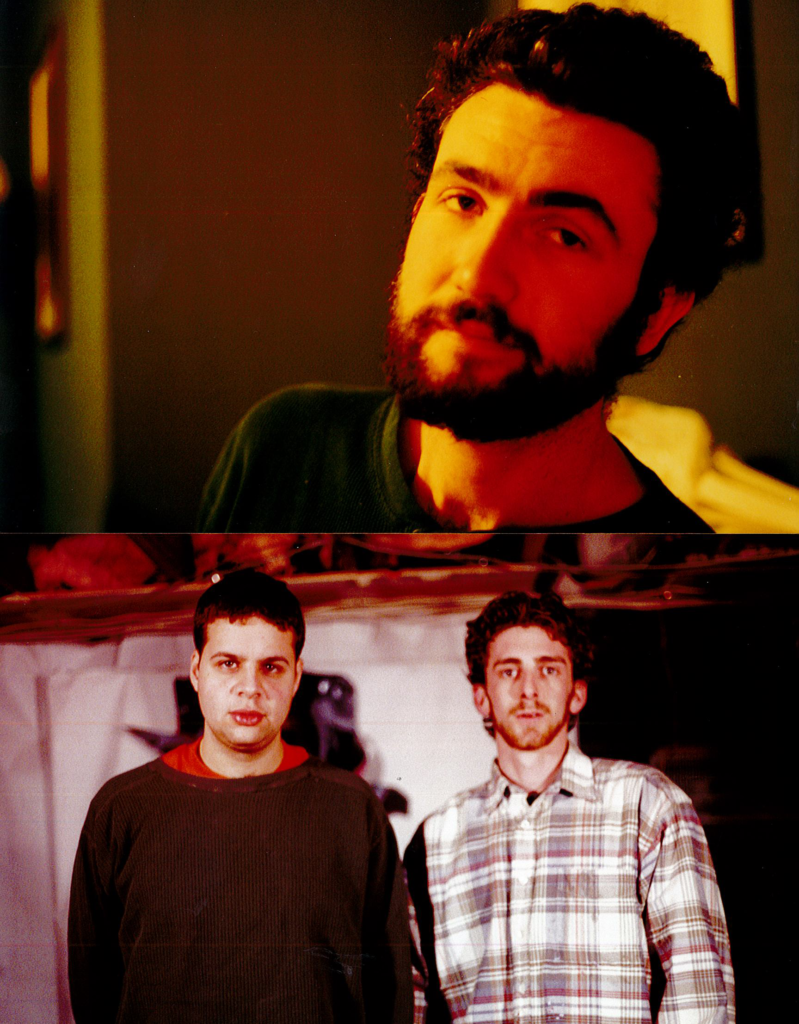

Rick had been cremated, so there wasn’t a viewing, just an arrangement of flowers to the right side and a blown-up photo of him on the left. It must have been a much younger photo. He looked to be in his early-twenties in it. Less grizzled than the last time I’d seen him at the bar from a few tables away: wooly blonde beard, greasy slicked back hair and sunglasses in a room that was already dark. In the photo, he was wearing one of the Perry Ellis shirts he’d favored back then. He’d wear these expensive shirts with ripped blue jeans and large hulking basketball sneakers. Shaquille O’Neals or Jordans. But of course, the photo cut off at his waist. It reminded me of a portrait Lex had painted of him when Lex had started painting. A portrait that had made me ask for one too. A commission. I’d paid him for materials, canvas. And he’d made me a painting in the style I’d admired. Lush fauvist colors. Thick globs of swirling emotion in the mode of Van Gogh. Rick’s portrait had held a place of honor on his bedroom wall behind the TV he played his Playstation on.

Sonny had been the first to arrive at the parlor. He was waiting out front as Jim and I arrived, and Lex showed up, and we all shook hands. We took our seats off to the side, together, and talked. Most of our talk was in whispers, and most of it led to laughter in the silent room. It might have been inappropriate, but we were telling each other our memories of Rick, the good ones, and they were truer than the bullshit his father was peddling about some mythical “golden boy” who’d never existed. Most of the things we shared were goofy stunts he pulled. Because he was goofy. There was no denying that. He was uncoordinated. He’d never been good at sports, but he always showed up to play. He always engaged with all his heart.

“Remember that time he came to the court? And he had that North Carolina jersey. Blue and white. Whole outfit, shorts and everything. Only the jersey didn’t have a number, so everyone called him water boy.”

“He was always almost there with his style. Headed the right direction but not quite pulling it off.”

“And Brian Dougherty hoisted him up to dunk the ball, and the shorts were too big so they fell down.”

“Remember that time those dudes at the courts were fucking with him, and he got up in arms and was all defending himself, and we were like, good for you Rick. Don’t let ’em get to you. And he just had to finish up by telling those dudes to suck his cunt. It was some of the funniest shit I ever heard. I’m not sure he knew what it meant.”

We couldn’t contain ourselves. We kept laughing. It was the closest to a Big Chill-moment we would have, sitting, sharing our memories. After the service, Sonny was wrecked. He couldn’t talk to us, or maybe didn’t want to. Maybe the sting was present in seeing us again of how we’d left things all those years ago. In any case, he took off. Maybe he went home, maybe he went out to drink. The rest of us retired to the Keswick Coffee shop across the street, and had a cup of coffee, but Lex looked ready to go. I had the feeling he didn’t want to stick around in Glenside too long. He’d run as far as he could from this place, and he seemed to look as though returning, closing that distance and coming back, might trap him here. As though, now that he was here someone might not let him leave. Then again, he’d fallen out with Jim too, and though I’d let bygones be bygones, though I’d greeted Lex with warmth, he was seated across from two people he’d been close with and pushed away.

As we went across the street, Lex asked Jim to hang back with him and I was left to make forced conversation with Lex’s wife. I had met her before. Before the fallout, or maybe during the fallout, I’d gone up to New York and spent a night with Jim and Lex and her, and she and I had talked. She wanted to know about Lex. More about Lex. And we went barhopping and I revealed as much as I knew about her prospective husband, which was everything a friend could know. In short, I was loyal and told her how great Lex was. And later, when she came to New York from Germany and was in grad school, Lex called me and asked me to edit her thesis, which I did. But I never became friends with his wife, so we sort of shuffled along, trying to talk, while Lex and Jim hung back. When they finished they caught up to us, and we sat in silence and drank coffee. The conversation was stilted. I could tell Lex wanted to leave, and as soon as he could, he made an excuse and he and his wife rose and left. When they were gone, Jim and I walked back toward my parents’ house. He’d parked across the street.

“What were you talking about?” I asked. It was really none of my business, but I couldn’t avoid being curious. And Jim understood. He knew that in spite of falling out, I was curious about Lex, so he indulged me.

“Just what happened when they stayed at my apartment,” he told me.

This was what their falling out was about. Lex and his wife had had to stay with Jim for a while. The building where they lived had been condemned. They had to move out and find a new space to live. And in the meantime, Jim had let them stay at his apartment with him. While they’d been there, they’d fought with each other, and Lex had fought with Jim. The situation had become tense, and finally it gave. Jim and Lex were at odds. They found a new place and Lex and his wife moved out. And him and Lex weren’t on the best of terms.

“I’m glad I didn’t listen to him,” Jim had told me before this. “He tried to turn me against you, but I remained neutral. But I get what you meant at the time.”

Jim had pulled out from under his influence. I’d explained it to him when Lex and I had fallen out. As long as I was deferential and acted the part of little brother, he had use of me. As soon as I demanded he treat me as an equal, he had no use for me. It was the same for him and Jim at this point. And yet, Lex must have been feeling the solitude.

“So what did he say about it? You and him?” I asked.

“He told me he was sorry,” Jim said.

Oh, how that fucking rankled! Lex was gone. He’d swooped into town to show his face at Rick’s service, apologized to Jim, said as few words to me as possible, and gone his merry way. I could concede I’d acted like an asshole when we’d fallen out. But I still thought Lex was at fault. I figured at some day he would apologize to me. But he didn’t. Jim had gotten an apology. He barely spoke to me. Still, I searched and found it in myself to forgive him. Maybe I’d have to take the lead at some point. A mutual apology started off by me. It wouldn’t be the first time. The question was, did I really want to reconnect with him? Sometimes I did, but I wasn’t ready to admit fault just yet.

There are no comments yet